Paradoxes

Back in freshman year of college I took an English course based around time travel, a topic I’ve always loved to think about. Below is the final paper I wrote for the course (including citations). Enjoy!

The Paradox of Temporal Paradoxes

Dictionary.com defines a paradox thus: “A seemingly contradictory statement that may nonetheless be true.” It comes from the Greek word “paradoxos”, meaning conflicting with expectation. Temporal paradoxes, therefore, are instances where the outcomes of specific actions conflict with expectations. However, it is the opinion of this writer that when the ability to travel through time is finally discovered, no paradoxes will occur because whenever people try to change anything in the timeline, they will find that their change only fulfills it.

Temporal paradoxes can be divided into two overarching categories – the grandfather paradox, and the predestination paradox. The grandfather paradox is not so much a single paradox, but the many possible outcomes of a specific action, namely, going back in time and killing one’s grandfather before he meets dear old grandma. The outcome depends entirely on the type of resolution. The parallel universes resolution claims that whenever a person goes back in time and changes something, a parallel universe is born, thus not affecting the timeline from which the time hopper came. Many Science Fiction writers like this particular resolution. In the novel The Man Who Folded Himself, by David Gerrold, Daniel Eakins creates so many alternate timelines that he begins to run into alternate versions of himself who are following his footsteps and time traveling as well. Using a device called the timebelt, he hops around his timeline changing events to see the outcomes (Gerrold). The relative timeline resolution states that the universe has no absolute timeline. Instead, it relies on the assumption that humans can create their own timeline because each individual particle of which they are made has its own timeline, Therefore, killing grandpa is not only possible, but will not end in the traveler disappearing. Rather, since each particle has its own timeline, the traveler will continue existing, making any changes they would like. The complication with this resolution is that once the grandfather dies, the particles that make up the time vagrant suddenly lack a history. This is not so much the problem as the fact that without a history, energy (in the form of particles) will seem to have appeared out of thin air. The first solution to this problem states that the universe has infinite energy, while solution two postulates that by traveling back in time, the traveler removes energy from the future, and takes it with him into the past. The restricted action resolution (probably the most well known) states that while time traveling, you cannot do anything that will stop you from making the trip back in time. Therefore, if the traveler wants to kill grandpa, the “shot fired at the traveler’s grandfather will miss, or the gun will jam, or misfire,” or any number of things will happen, but somehow grandpa survives (Grandfather 1). The major implication of this is that there is no such thing as free will. The destruction resolution is the simplest of the lot. It simply states that by changing your past (shooting grandpa), you will cause the destruction of everything that you ever affected. Think of It’s a Wonderful Life, only with possibly wider ramifications. In Back to the Future II, Marty claims that if a paradox is created, it could unravel “the very fabric of the space-time continuum.” It is this kind of widespread destruction that coincides with the aptly named destruction resolution.

Predestination paradoxes, sometimes called a causal loop, relies on the assumption that by traveling back in time, time is not changed, but the traveler merely fulfills their part in an action that has already occurred. One such example is from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. When traveling back in time using the Time-Turner, Harry saves his and Sirius’s life by casting the Patronus spell. By coming back in time, he did not alter the timeline; he fulfilled his job in ensuring that the events occurred. The paradox is that, by surviving because of his own Patronus spell, he was then predestined to return to that time to save himself. Mind-boggling examples like this one abound in reference to Predestination paradoxes. Another such example comes from the article “Predestination Paradox” on Wikipedia.com:

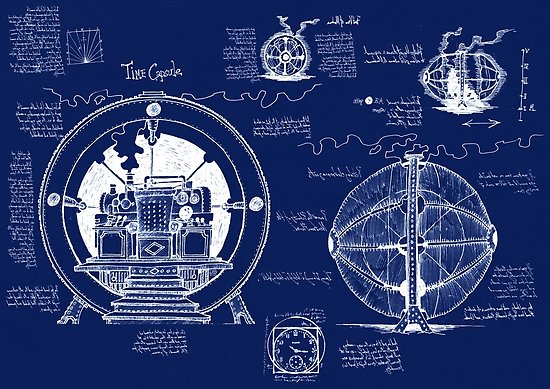

Another form of the Predestination Paradox is called the Ontological Paradox. This paradox centers on some piece of info or else something material having no origin. Complicated? Yes. Another example from the “Predestination Paradox” article makes this explanation:

The paradox is: where does the schematic that is handed down originally come from? There is no explanation for this paradox. The plans exist merely because a Predestination paradox forces them to be passed down from future to past. This is extremely convoluted to say the least.

The overlap between the restricted action solution of the Grandfather paradox and the Predestination paradox is paramount. In a way, the coincidence of two separate theories gives strength to the subject of the overlap. An example comes from The Time Machinemovie. The Time Traveler, having seen his fiancé murdered, builds a time machine and attempts – unsuccessfully – to save his fiancé’s life. But every time he saves her something else happens, and he is forced to witness her death yet again. According to the restricted action solution of the Grandfather paradox, he cannot change the timeline in such a way that will stop him from making his trip back in time. Therefore, he cannot save her life because without her death, there was no reason for him to build the time machine and travel back in time. If thought is applied, this particular theory about paradoxes perhaps makes the most sense. How can a time traveler go back in time and do something that would then stop the temporal trip from occurring. It also makes sense, no matter how mind boggling, that any changes made on a trip back in time would merely be fulfilling an action that has already occurred. This simpler explanation (even if still not so simple) is why this particular theory is easiest to internalize.

On the whole, paradoxes are extremely stimulating intellectually. Interestingly enough, many philosophers believe that because of the possibility of paradoxes being formed by time travel, time travel is therefore impossible (Pickover 35). (Sounds suspiciously like circular reasoning.) However, there are other explanations that allow for time travel, but discount the existence of paradoxes. According to “The Novikov self-consistency principle and recent calculations by Kip S. Thorne … there are no initial conditions that lead to paradox once time travel is introduced” (Grandfather 1). This particular theory can be slightly modified to encompass the relative timeline resolution mentioned earlier. Along the same lines, Greenberger and Svozil, using pages of very complex and complicated mathematical equations and theorems, believe that, “No matter how unlikely the events are that could have led to your present circumstances, once they have actually occurred, they cannot be changed” (Greenberger 10). In effect, the time traveler is merely an observer and cannot change anything because of the changes potential effect on his temporal travel.

Despite this seemingly scientific evidence, time travel is still a theory, an ephemeral dream of science-fiction writers around the world. Any speculation on potential outcomes is just that – speculation. We will never truly be able to determine the existence or nonexistence of paradoxes until the ability to traverse time is discovered. Until we can know for sure, the Predestination Paradox and the restricted action resolution seem to make the most sense of all the theories, and the intellectual fun remains in the imagination.

Gerrold, David. The Man Who Folded Himself. Dallas: Benbella Books, 2003. Gerrold Dot Com. Benbella Books. Retrieved 29 Sept. 2005. [http://www.gerrold.com/fiction-folded/page.htm]

“Grandfather Paradox.” Wikipedia.com. Updated 28 Sept. 2005. Retrieved 28 Sept. 2005. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grandfather_paradox]

Greenberger, Daniel M and Karl Svozil. “Quantum Theory Looks at Time Travel.” Quo Vadis Quantum Mechanics?. Ed. A. Elitzur, S. Dolev and N. Kolenda. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 2005. Retrieved 28 Sept. 2005. [http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0506027]

Pickover, Clifford A. Time: A Traveler’s Guide. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

“Predestination Paradox.” Wikipedia.com. Updated 26 Sept. 2005. Retrieved 28 Sept. 2005. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Predestination_paradox]